The Enduring Power of Gandhi’s Legacy in Shaping India

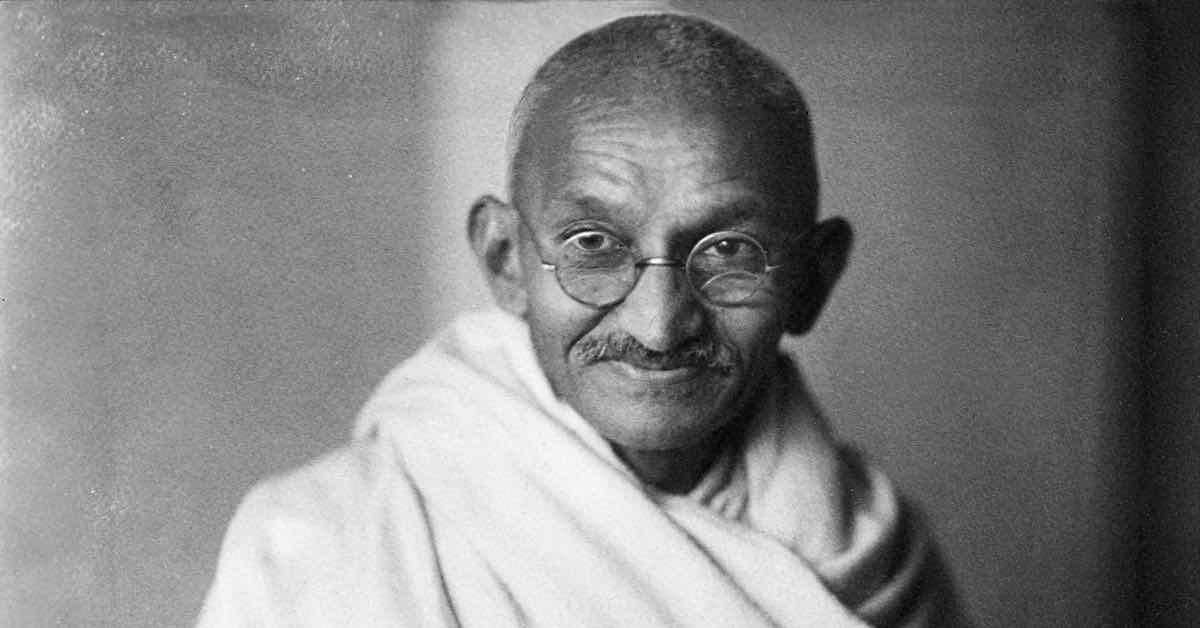

I am not someone who blindly glorifies Mahatma Gandhi nor am I someone who despises him; I fall somewhere in between where I hold immense respect for what he stood for while also acknowledging the deep differences I have with many of his ideologies. There are certain aspects of his perspective that I find problematic to the point of disgust and some actions of his that I cannot reconcile with.

Yet, when I step back and look at the larger picture, I cannot deny that without Gandhi the India we see today might not even exist in the same form. He was a pioneer in uniting Indians under one motion of freedom; he gave the people a collective consciousness and a sense of direction. The country was built on a mixture of his ideologies, his proclaimed principles, the causes he embraced, and the many things he ignored; but in the end Gandhi was a human being with all the flaws and contradictions that come with that.

To start with the bigger picture, Gandhi emerged as a figure who could stand above the fragmented political scene of India and become a unifying presence. One can argue that even without Gandhi independence would have arrived, perhaps through different methods and under different leaders. Subhas Chandra Bose and his approach, for instance, could have achieved results, but Bose’s reliance on Axis alliances during World War II might have left India with long term damage and compromised sovereignty. What Gandhi provided was a moral framework and a legitimacy that resonated with the masses.

I often think of the Tilak Swaraj Fund when people with barely any financial security came forward and offered their jewelry to support the Indian National Congress. That was not a normal political fundraising exercise; it was the aura of leadership that Gandhi carried, the saint like stature that made people transcend their personal struggles. It was this ability to embody sacrifice and simplicity that united India, and without him a fractured post independence order of princely states was a very real possibility.

His principle of non violence, as subtle as it may sound, was nothing short of revolutionary. Non violence was not Gandhi’s invention in the strict sense; there were precedents in Mohism in China, in the Jewish revolts against Pilate to preserve the Torah, and in the writings of Henry David Thoreau whose Civil Disobedience of 1849 deeply influenced Gandhi. He was equally shaped by Leo Tolstoy’s Christian pacifism and of course by the Jain and Buddhist doctrines of Ahimsa.

What Gandhi did differently was to elevate this principle from a moral or philosophical guideline to a mass political strategy. With satyagraha he transformed non cooperation into a weapon that needed no sword or gun but displayed the raw strength of people united. This approach, whether one agrees with all its outcomes or not, is something that became part of India’s soul and part of the vocabulary of global struggles.

It is also important to note that Gandhi’s rise was not in isolation; leaders before him had already prepared the ground. Bal Gangadhar Tilak had pioneered mass mobilization through cultural festivals like Ganesh Utsav and through newspapers, making nationalist politics accessible to ordinary people. Gandhi built upon this foundation when he returned from South Africa in 1915. He had seen racial discrimination firsthand in South Africa and had already tested satyagraha there.

In India, his Champaran Satyagraha of 1917 and the Kheda Satyagraha of 1918 showed how he took Tilak’s methods of mobilizing peasants and infused them with his own insistence on non violence. Tilak and Gandhi had differences; Tilak was not opposed to revolutionary violence in some contexts, but the fact remains that Gandhi admired Tilak’s ability to inspire and in many ways took his methods to a pan Indian scale. This was the shift from localized agitation to a national movement.

Yet, Gandhi was far from perfect and his limitations were stark when it came to social reform. His stance on caste was deeply problematic; while he did attempt to uplift Dalits by calling them Harijan, meaning children of God, the reality was that he remained a staunch believer in the varnashrama system. He went so far as to suggest that Dalits should see their role as nurturing higher castes, which indirectly reinforced the hierarchy he claimed to oppose.

Gandhi was orthodox in many of these ways and while he evolved in some respects by the early 1940s, one cannot ignore that his social vision was often regressive. In contrast, leaders like B R Ambedkar called out this hypocrisy directly and refused to settle for symbolic elevation of caste identities. Gandhi’s moral authority in politics did not always translate into progressive positions on society.

Another area that always draws criticism is his personal practices, especially his experiments with celibacy which remain highly controversial. These were part of his attempt to discipline the body and mind, but they often come across as disturbing and ethically questionable. Here again I remind myself that Gandhi was human, and he had flaws that were magnified because he was constantly in public view.

But despite these failings, he was not the divider of India as some narratives try to paint him. His role in the partition of India was minimal compared to the intransigence of Jinnah and the divisive policies of the British. Gandhi’s fasts in Bengal and Delhi during 1946 and 1947 were desperate attempts to hold communities together and prevent bloodshed, even if he could not alter the course of events.

It is also a misrepresentation when people say Gandhi abandoned Bhagat Singh. During the Gandhi Irwin Pact negotiations in 1931 he did appeal to Viceroy Irwin to commute Singh’s death sentence. It can be argued that Gandhi’s efforts were restrained because he did not want the pact to collapse, but it is wrong to say he was indifferent. This shows again the complexity of Gandhi’s role; he was a man of many errors, many corrections, and constant evolution.

The tragedy is that in trying to build him into a godlike figure, the Indian National Congress and later sections of society stripped him of his humanity. For me Gandhi is not a god, not a flawless visionary, but a man who shaped a country through his convictions and contradictions. He was essential in uniting India but he remains someone whose ideas must be critically examined rather than blindly worshipped.